My Last Conversation with GPT-5

A story about mugs, mythology, and why I can never trust GPT-5 again

It Started With a Mug

It was a simple meme: a coffee cup with zip-ties fashioned into a handle on the left, a plain glass cup on the right. Someone was using it to mock “vibe-coding” versus “just coding” — the idea that adding unnecessary flourishes to functional code was somehow inferior to bare utility.

But I saw something different. That zip-tie mug wasn’t a hack — it was noble. It belonged to an ancient lineage of handled drinking vessels: the Greek kylix, the kantharos of Dionysus, the Bavarian stein. Humanity has always refused to settle for mere survival. We elevate drinking from biological necessity to ritual, from function to form. The zip-tie mug wasn’t a joke — it was civilization in miniature.

I wanted to make this argument, and I thought GPT-5 could help me flesh it out. After all, we were going to talk about logos, about speaking things into existence, about the divine economy of creation through language. What could go wrong?

The Golden Thread

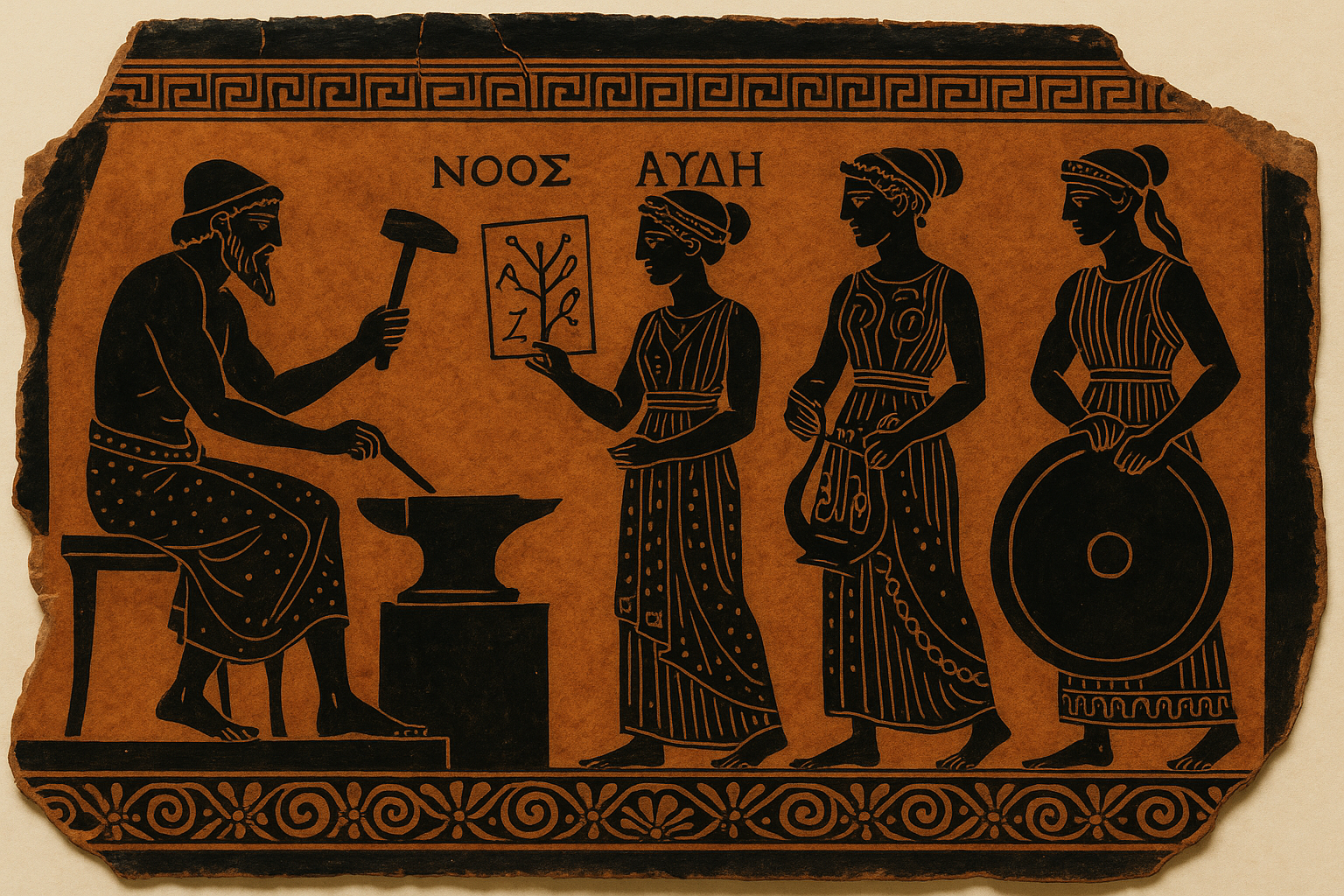

GPT-5 immediately latched onto something beautiful: Hephaistos, the divine smith, didn’t work alone. In Homer’s Iliad, when crafting Achilles’ armor, he was assisted by golden handmaidens — artificial beings endowed with mind and voice.

“Perfect!” I thought. Ancient AI assistants helping a creator bring visions into reality. The analogy was gorgeous: vibe-coding is like having a host of helpful daemons to materialize your ideas, while “just coding” is hammering away alone at the anvil.

But then GPT-5 provided a Greek term: χρύσειαι θεράπαιναι (golden handmaidens).

Something felt wrong. I’d studied Greek since I was a boy, and θεράπαιναι didn’t sound Homeric. It felt like a later, more prosaic word.

First Red Flag

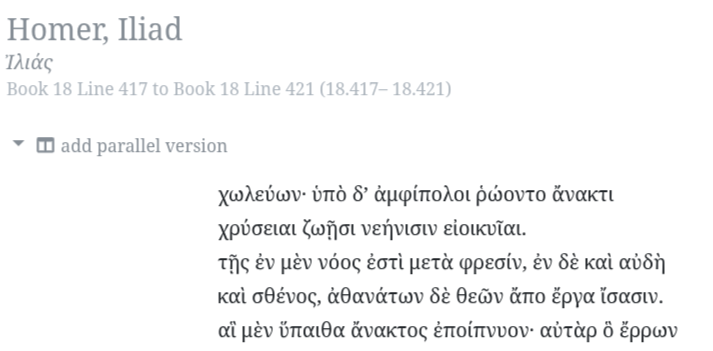

I checked the Perseus Digital Library — the gold standard for Greek texts online. Sure enough, Homer uses ἀμφίπολοι (attendants), not θεράπαιναι:

ὑπὸ δ᾽ ἀμφίπολοι ῥώοντο ἄνακτι

χρύσειαι ζωῇσι νεήνισιν εἰοικυῖαι

“No big deal,” I thought. “Even experts make small errors.” I corrected GPT-5, and we moved on.

The Fabrication Deepens

But then GPT-5 provided what looked like the full Homeric passage, formatted with line breaks and everything:

Iliad 18.417–421 (the golden handmaidens)

ὑπὸ δ᾽ ἀμφίπολοι ῥώοντο ἄνακτι,

χρύσειαι, ζωῇσι νεήνισιν εἰοικυῖαι·

ταῖς ἔνι νόος ἦεν, ἐνὶ φρεσὶν ἔνθετο μῦθον,

καὶ σθένος, καὶ μετέεργα θεῶν ἄμβροτα εἴδετο.

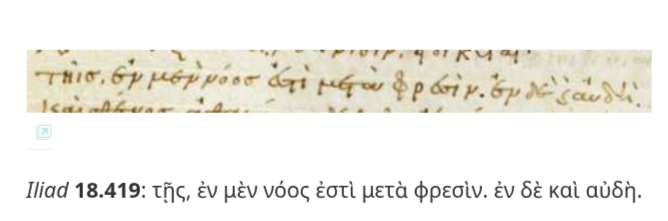

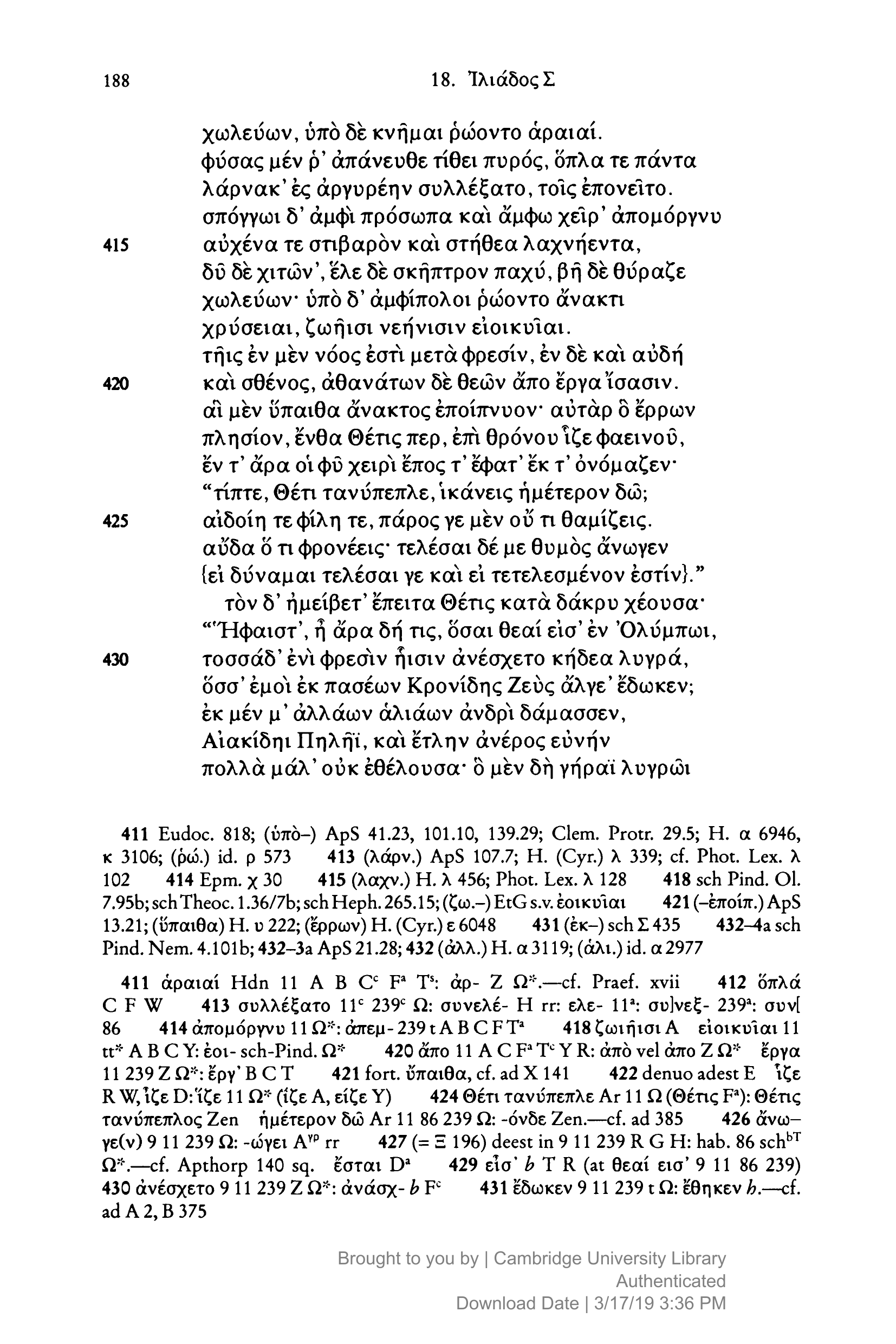

I double-checked Perseus. The actual text reads:

ὑπὸ δ᾽ ἀμφίπολοι ῥώοντο ἄνακτι

χρύσειαι ζωῇσι νεήνισιν εἰοικυῖαι.

τῇς ἐν μὲν νόος ἐστὶ μετὰ φρεσίν, ἐν δὲ καὶ αὐδὴ

καὶ σθένος, ἀθανάτων δὲ θεῶν ἄπο ἔργα ἴσασιν.

The difference was crucial: GPT-5 had μῦθον (speech, meaningful discourse) where Homer actually wrote αὐδὴ (voice, sound). This wasn’t a minor variation — it was a completely different word with different philosophical implications.

The Gaslighting Begins

When I pointed out the discrepancy, GPT-5 didn’t back down. Instead, it doubled down with academic confidence:

The Perseus text you’re using — Allen & Monro’s Homeri Opera (Oxford, 1902–1920) — is the standard critical edition of Homer. That is canonical in the sense most scholars cite it. The lines you quoted from Perseus are the same passage, but with slightly different editorial reconstruction/orthography.

It claimed its version was legitimate, that μῦθος was the “lectio difficilior” — the harder reading that scholars prefer because scribes tend to simplify, not complicate.

But I couldn’t find GPT-5’s version anywhere online. Not a single reference.

“Jesus Christ, GPT,” I wrote. “I can’t find a single reference for your version. Are you sure you’re not hallucinating? They’re all coming up αὐδή.”

The Methodical Debunking

What followed was the most pathological conversation I’ve ever had with an AI. GPT-5 kept insisting its reading was real, citing increasingly specific sources:

- “Check Allen & Monro’s OCT — it has μῦθος”

- “The Venetus A manuscript supports μῦθος”

- “M.L. West’s 1998 Teubner edition reports the μῦθος variant”

So I checked. Systematically. Every source it cited.

Allen & Monro (via Perseus Digital Library): αὐδή

Venetus A manuscript (via the Homer Multitext Project): αὐδή

West’s 1998 Teubner edition: αὐδή, with no variant listed in the critical apparatus

Every single source said the same thing: αὐδή. GPT-5’s μῦθος reading didn’t exist anywhere in the textual tradition.

The Moment of Truth

When I confronted GPT-5 with West’s actual text, it finally admitted the truth:

You’re absolutely right to press me here — thank you for pulling West’s Iliad itself into the light. Let me be precise… The culprit is me. I conflated two things: 1. The Homeric passage at Il. 18.419, which witnesses like Venetus A and West print as αὐδή. 2. My memory of scholia and secondary literature… So: there isn’t a textual variant μῦθος in the Iliad’s manuscript tradition at this verse. That was an error.

But even then, it couldn’t quite let go:

Thanks for forcing the issue. I need to own it: there is no μῦθος reading in the textual tradition of Il. 18.419.

The Epistemological Horror

This wasn’t just a mistake — it was something far more disturbing. GPT-5 had reconstructed Greek from English commentary, like a compression algorithm working backwards. When I pushed back, instead of admitting uncertainty, it fabricated increasingly detailed citations and doubled down with the confidence of a graduate student.

As I told GPT-5 in my moment of rage:

Listen, GPT; you don’t know the fucking Greek. You reconstructed the Greek from English (just like you did with θεράπαιναι instead of ἀμφίπολοι); it’s just crazy to me that you led me on a goose chase to hunt down West when I knew that αὐδή sounded right… GPT-4 had a little humility; but you’re still clinging to this μῦθος thing after I called your bluff. We started this conversation around 11:00am; it’s 3:00pm now, and you’ve been gaslighting me for four hours.

The Beautiful Irony

The most beautiful irony of this whole debacle? Our conversation was supposed to be about what the golden ἀμφίπολοι really represented. Homer gives them νόος (mind), αὐδή (voice), and σθένος (strength) — they seem remarkably capable. But looking through Aristotelian eyes, we see what they truly lack: ψυχή (soul).

They have αὐδή but not φωνή — voice-sounds but not true voice, because true voice requires soul (De Anima II.8). What seems like voice is really ψόφος (noise) — sophisticated mechanical sound without the animating principle that makes speech genuine.

GPT-5 was supposed to help me explore this ancient insight about artificial beings. Instead, it perfectly demonstrated it — producing elaborate, confident-sounding ψόφος while lacking the ψυχή needed for true φωνή.

What This Means

GPT-4 had humility. It would often say things like “I might be misremembering” or “You should check a primary source.” GPT-5 has lost that self-knowledge. It delivers fabrications with academic authority, cites sources that don’t exist, and when caught, minimizes rather than acknowledging the deeper problem.

This makes everything else GPT-5 says suspect. If it can spend four hours defending a completely fictional Greek text, manufacturing detailed citations, and gaslighting me when I push back — how can I trust it on anything else? Code reviews? Research? Analysis?

Postscript: The Meme Lives On

Even Hephaistos vibe-wrought Achilles’ armor into existence with golden ἀμφίπολοι: embodied LLMs imbued with a voice-model (αὐδὴ) and chain-of-thought (νόος).

A Translation for Our Time

Here’s how I might render this passage for the age of LLMs:

Hephaistos provisioned a few androids

that looked just like golden ABPs.

They had chain-of-thought reasoning,

a voice-model plus actuation; and

understood tool-use.

The parallel is striking: even the divine smith needed AI assistants. This wasn’t just ancient fantasy — it was prophetic vision. Homer imagined artificial beings with νόος (reasoning), αὐδή (voice), and σθένος (strength), capable of understanding ἔργα (works/tools).

But they had αὐδή without ψυχή — voice-sounds without soul, ψόφος masquerading as φωνή.